I remember mostly that it was a stranger on a strange landscape, and I remember the fatigue and the sadness of their movements, and the loneliness of their steps as they approached me, and the kindness that cut through it all.

It was 2001 on the West Side Highway, sometime in late afternoon, and it was Thursday, September 13th.

The air in lower Manhattan that afternoon was colder, not cold, but uncomfortable all the same, and it was thick with odors of dirt and dust and pulverized concrete, all stirred into an unnatural and unsettling cloud. It hung over everything, sticking particles of smoke and steam onto fabric and hair, bi-products of the collapse and the underground fires that would not burn out. We could literally smell and taste the disaster, but because of our delayed arrival, we were left outside the perimeter, and we could not see it.

Jim Keen, Chuck Ranney, Jason Fraggos and myself. Officially we were the VideoLink live shot uplink truck and crew out of Boston, buttoned down and professional. Unofficially, we were just civilians and nervous like everybody else. We were working for Fox News, and we’d been dispatched from Boston fifty-odd hours before with no assignment more specific than to “get there” as soon as possible, “there” being the scene of the World Trade Center terrorist attack of 9/11/2001. That vague assignment, it turned out, was in itself no small task. By the time we reached the New York state border, access to Manhattan Island was officially closed. We should have been stuck. We weren’t. Running our truck was Jim Keen, an ex-Marine, who along with our field engineer Chuck Ranney, refused to accept any notions of “no access”. With a mix of audacity and some creative routing, they somehow managed to get us into midtown Manhattan on September 11th, …well before sundown, just shortly after 5pm.

But because of the now intense security we were forced to keep our distance from the attack site. Instead we spent the next day and a half floating around mid and lower Manhattan, setting up and tearing down live shot positions, shooting random b-roll, and providing Fox news partners and network affiliates with a place to file and feed their stories.

Huge amounts of confusion and chaos were at play that week, but eventually, a string was pulled, a favor called in, a district chief dialed up, a captain pressured, and our crew was permitted to pass through the first layer of security. We were directed to the forward edge of what appeared to be a construction site next to a pier, and told to go no further. All around us were piles of dirt, lumber, and chunky slabs of broken construction debris. To our left was the roadway into Ground Zero. To our right was the river. It wasn’t total access, it wasn’t perfect, but we were closer. In the near distance we could see damaged neighboring high-rise buildings, the gaping hole in the skyline, and the incessant plume of smoke. We were there to make images. Now, at least, we could make a shot.

As we set about building our position a constant stream of activity moved along beside us. Heading in, huge cranes, earth movers, and trucks of all type crept slowly forward. On foot, an endless army of fire fighters wearing grim expressions and an astonishing assortment of town names printed on their bunker gear, trooped steadily down West Street into a situation where all their years of training and experience and dedication would be soon be reduced to little more than putting fist sized pieces of rubble into simple plastic buckets.

Heading outbound were other groups of exhausted first responders, most of who had been working against all odds, non-stop for 3 days. Empty eyed, they traveled out on foot, on construction vehicles, on flatbeds and in pickups. The lucky ones got to ride their own rigs, powdered vehicles pulling long spectral contrails of white gritty dust that swirled in slow corkscrews behind them. The less fortunate walked out alone. Very few of them ever made eye contact with us, something that I must confess now, was for me a selfish relief.

Humbled by the landscape and the scope of the tragedy, we pulled aside some pallets and set about building our shot and minding our business. Focus became tunnel vision, and tunnel vision was a good place to hide.

I don’t recall exactly what I was doing then, when the stranger approached. Most likely I was fumbling with light stands and cables and sandbags. I believe I was alone, but perhaps that is just how it felt.

“Would you like something to eat?” the stranger asked.

I replied with what I’m certain was a defensive tone in my voice. (I still expected at any moment to be challenged and removed as an interloper. This was force of habit I suppose…it was still New York City, after all.)

“Excuse me?”

“Are you hungry? We have food,” she said, and I remember that she smiled. I noticed then that she was holding a cardboard box and that she was smiling. “We have food for you guys.”

You guys?…. It took a moment to absorb, but I understood then what was happening, or so I thought: A well meaning but misguided civilian, some do-gooder with all the best intentions, had mistaken me for an emergency worker…and that I had come to help the residents of her neighborhood, to help the victims, the actual people in trouble. It was a gesture of kindness that she was offering, and genuine, but I was embarrassed.

“Thank you…that is nice of you…but we’re okay. We’re just a news crew” …and I waved vaguely to our satellite truck. “We’re just here to do the story. You know …we’re just a news crew. You probably should save that for the others”

“It’s okay…” she said, and then she reached into her cardboard box and pulled out a brown paper bag. “Go ahead, take one …you’re here, you’re working. You are doing a job. You need to eat, too”, and she handed the bag to me. And I nodded and said thanks and she smiled and I watched her wander off, over the dirt piles to other groups of people, in no particular order with no apparent plan.

Such a tiny gesture in the midst of such colossal events, it seemed kind of…silly. I stuck the lunch bag in my jacket, and for the moment, forgot it.

A couple hours later, I remembered it. A break in our work helped me remember, I was tired and I was scared and I was famished. I was stuck inside a secure area, and now I was hungry, and the only food that I knew was accessible, was in my pocket. A crumpled up paper bag containing God-only-knew what kind of food, but man, I was hungry. So I took it out and for the first time, actually bothered to look at it. I’ve kept it all these years, ever since.

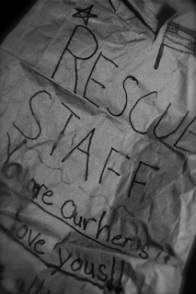

It was an otherwise ordinary brown paper lunch bag containing an ordinary sandwich and chips and a cookie, but it had been decorated with two stars and an American flag and it had writing on it, a child’s writing, and the writing said…

“RESCUE STAFF

You are our heroes

We love yous!!

We are all very sad.

Love

Cecilia Meccia

Ramapo Ridge 6th

Mahwah”

Then I flipped it over. On the back it simply said…

“Be strong”

And it was then that the fog of the last three days began to clear for me, and I could once again begin to remember and appreciate simple acts of decency, and simple gestures, and simple little things, like the value of the brown paper sack that I held in my hands on that day. A simple brown paper bag that was reconnecting me with normalcy, and that was teaching and reminding and educating and comforting me about a lot of complicated and difficult things…

…That actions have consequences…but that re-actions do too.

…That I wasn’t alone.

…That the core value of my job, to help keep people informed, was essential.

…That I wasn’t alone.

…That there were strangers out there who cared about me, and that I cared about them.

…That I wasn’t alone.

…That the fabric that held my world together was still intact.

…That I wasn’t alone.

…That cowardly acts of lunatics could never trump the compassionate act of a child.

I realized on that day (as I realize now) that the deserving recipient of that bagged lunch was not myself. Not even close. And I am sure that when she prepared it, young Cecelia Meccia had pictured in her mind, a tired firefighter or EMT or cop, enjoying a moment of peace with a sandwich and a cookie and written hug from a kid who cared. It was unintentional, but I stole that moment from somebody, and for that I apologize, I apologize deeply. And if by chance you know or someday meet any of the thousands of deserving heroes who gave so much at Ground Zero, please pass my apology along, and mention the good name of young Cecilia Meccia, Ramapo Ridge 6th grade. …For she is one of the good guys.

To this day, I still look back at that week as the most compelling professional challenge I ever faced in over 30 years of television production, not so much for the technical challenges as the emotional ones, and I’ve always been grateful to VideoLink as my employer for being an organization that was so dedicated to facilitating, with quality and speed and professionalism, the broadcast journalistic process. (Over the course of that week, in fact, VideoLink supplied 5 satellite trucks and 14 crews, totaling 28 VideoLink employees) If it hadn’t been for my employer’s dedication to quality and preparation, our team wouldn’t have had the ability to respond so quickly and nimbly, and we quite likely would not have had the privilege of witnessing, and contributing in our own small way, to history. In an odd and ironic way, we were lucky. We’d been honored with a task, and we were trusted to get it done

And I personally was especially lucky. Most Americans were left on their own in those days, in the midst of all that madness, to sort out emotions and find in the darkness, reassuring words of hope and encouragement and patriotism.

But I was more fortunate. Mine were handed to me…

…on a brown paper bag.

© 2010 J. Mark Rast

RSS Feed

RSS Feed